The role of shit in the Christmas story is predictably neglected

Yes, that's an inflammatory headline designed to make you read on. But it's also true.

You won’t hear the word ‘humiliation’ in many Christmas sermons, TV ads, or Hallmark cards this festive season, but for me, it’s the word that most directly connects the original Christmas story to my lived experience.

Why humiliation? It's mostly to do with money, which is what Christmas is all about now. It's not the sound of bells that I hear when the season begins, it's the ka-ching of the cash register. I have a long, turbulent relationship to money, and therefore I have an awkward relationship with Commercial Christmas. I don't get buyer's guilt when I spend money on Christmas so much as buyer's shame, which became baked in during the first weeks of marriage. I happened to rent a Batman video without ‘consulting’ my young bride, who promptly told me to take it back because we couldn’t afford it. Yikes. You'd think I'd learn my lesson there and then. Nope. I just learned to hide my shame, which culminated years later with a hurried purchase of a Nintendo GameCube. Sitting in the driveway, I realised this could end in violence, so I did what I should have always done with purchases that would lead to trouble — I hid it in the roof.

So yep — humiliation.

But mercifully, humiliation isn't just part of my Christmas story — it's also at the heart of the original one — starting in a stable, where the cattle shit.

Shit is another word you won't hear in Christmas advertising, sermons or greetings cards this Christmas. But it should be. Miss it, and you miss the heart of the story. You might call this scatology theology — unearthing the deeper meaning of Christmas in its messy, humiliating context.

Shit is there at the beginning of the story, when the baby is born among the cow dung and straw. It's there at the end of the story too, during the crucifixion — a tool of execution that takes hours to fulfil, during which time the condemned man, as well as bleeding and suffocating to death, evacuates his bowels, so that by the time he finally gives up the ghost he is stained by his own piss and shit, all of which takes place in view of family and followers, who just a week before saw him proclaimed with fanfare as a king among his people.

That's some bookend to a brief but extraordinary life.

The genius writers and poets who try to make sense of all this don't miss the scatology in the story like your advertising executives and salaried pastors and content providers do. They get it, and write extraordinary things about it.

The writer of the New Testament letter to the Hebrews, for example — creatively and ingeniously reframing this whole story in terms of temple sacrificial practices — reminds his readers that when the high priest carries the blood of the sacrificed animals into the most holy place of the temple, the 'bodies' of the animals are burnt outside the camp. By 'bodies' he means the hide, the flesh, and, most importantly, the faeces in the guts. The shit. We know ‘bodies’ means this, because it spells it all out back in Leviticus in the OT. These leftover bits are so ceremonially unclean that the person who takes them outside for the burning has to have a bloody good wash before he's even allowed back in the camp.

The writer then says this about Jesus, the same Jesus who was born in shit and straw: that he died 'outside' the city, where the animal shit is disposed of. A poetic parallel that he calls Jesus' disgrace.

An extraordinary thing to write about the person you're also saying is the son of God.

The writer hasn't created this symbolism out of nothing. It has an ancient context. In the book of Malachi, which in a Bible consisting of both Old and New Testaments is the last book before you get to the Christmas story in Matthew, the temple priests have been caught sacrificing 'unclean' animals, as well as committing other acts of corruption, and God isn't happy. He's livid. So God, in the words of the poet-prophet, says to the priests that he will smear their faces with the faeces from the sacrificial animals, as well as the faces of their descendants, and let them be carried off with it. Carried where? The implication is clear: outside the camp, where they'll be burned up with everything else that's unclean.

Jump forward in time, and back to the book of Hebrews, and this threat gets flipped around, in a narrative and poetic reworking that completes this scatological arc of the Christmas story — the God who issues the judgment, the same God who chooses to be born in a cattle shed, ultimately takes the place of the priests and dies as the ceremonially unclean portion of the sacrifice, fit only for burning.

If only one of those early writers had scrawled in the margins of the scroll, "He took shit for them", we wouldn't miss this element of the story. Which is a key element, especially when we reflect on such topics as the meaning and purpose of power in the contemporary world.

One of the purchases that caused me most humiliation over the years was a CD of U2's album How To Dismantle An Atomic Bomb, released 20 years ago last month. I know that it was the 20th anniversary last month because to mark the occasion, U2 released a vinyl boxset containing the original album, a shadow album, a live concert, and other bits and bobs. It cost a pretty penny. But I bought it — and reflexively hid it in the roof.

Halfway up the stepladder I recalled the original CD that I bought 20 years ago. Back then, I didn't settle for the standard CD release in the jewel case — I bought the deluxe version, which contained a hardback book that I had assumed would contain the album's lyrics. When I saw that it contained not lyrics but Bono's childish drawings and handwritten notes about stuff that didn't seem to make sense, I rang the shop and told them I was bringing it back for a refund. Which triggered an emotional spiral that evoked Batman VHS rentals and hidden GameCubes.

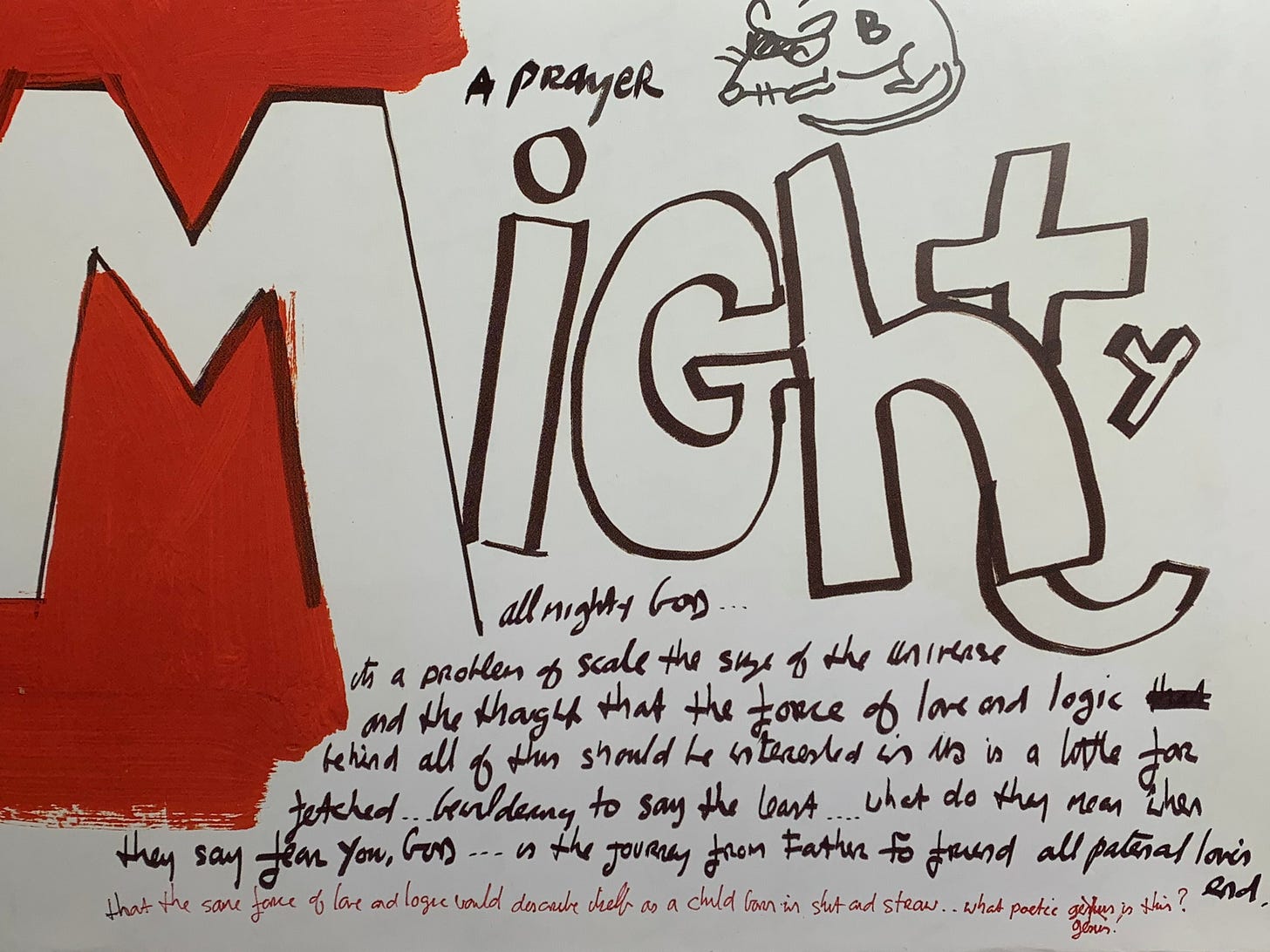

Before taking the CD back, I had a closer look at Bono's sketches and realised I'd been too hasty — that this was a work of genius. I've written about this elsewhere, so feel free to go hunt for the whole account and a longer discussion about the amazing contents of Bono's book. For the sake of this discussion, I want to highlight just one of the pages in the book, in which Bono redefines the word 'mighty'.

Bono sketches himself as a mouse. A mouse in fly sunglasses, with a B on its back. He calls this a prayer, and writes: All mighty God ... it's a problem of scale the size of the universe and the thought that the force of love and logic behind all of this should be interested in us is a little far fetched ... bewildering to say the least ... what do they mean when they say fear you, God ... is the journey from Father to friend all paternal love's end?" And then down the very bottom of the page, he writes in red: "That the same force of love and logic would describe itself as a child born in shit and straw ... what poetic genius [crossed out] Jesus is this?"

Which is a different take on humiliation, where the Christmas story is concerned. Humiliation not as weakness — such as the humiliation of hiding a purchase in the roof so your wife doesn't clip you round the ear — but a revolutionary reimagining of divine power as self-emptying love.

There's a deep paradox at the heart of the Christmas story. If most of what you know about the story is based on the Christmas carols, you'll probably have the impression that after the birth of the messiah there's a great fanfare about how it inaugurates a new era of peace on earth and goodwill to all people. But the reality is, nothing much changed. And 2000 years later we seem further away from 'joy to the world' and 'peace to all men' as it's possible to get.

The paradox seems to have more to do with how the proclamation of peace is understood than whether or not it's had any impact. If divine might is understood as unyielding power, then of course the absence of peace in the world is a massive fail. But perhaps the imagery of the shit and straw is as vital to understanding the proclamation of peace as it is to understanding divine might. If the proclamation of peace isn't a declaration that 'peace to all men' is going to happen whether we like it or not, but an invitation to a form of peace that is never anything other than vulnerable, self-emptying love that embraces weakness and humiliation and is a message of hope to those on the 'outside', then we play a key role in nurturing that peace. We can also get it massively wrong — from what we do in the home to what we allow to take place on the larger geo-political stage.

A call to peace from a divine life bookended by shit — in the cattle shed and at the temple sacrifice — is fragile, yet somehow it endures. We’re still celebrating Christmas, and the peace it promises quietly persists, perhaps less obviously in the bright lights of the shopping mall or the corridors of ‘power’, and more genuinely to those on the outside, where shit happens.