A peculiar greeting

What’s the deal with “brothers” in Colossians 1:1-2. I grew up in the “Brethren” and this gives me the heebie jeebies.

Paul, an apostle of Christ Jesus by the will of God, and Timothy our brother,To God’s holy people in Colosse, the faithful brothers and sisters in Christ:Grace and peace to you from God our Father.

What’s in a greeting?

Turns out a lot, when you spend some time with it. And I’ve spent a lot of time in Colossians over the years, as both a theological student and pastor/preacher, which is why I’m dipping back into it now for this first article under Burning Belly: The text is fire. Each Monday my intention is to exegete a section of the text, followed by some reflection on it within a cultural context on Wednesdays, and a more personal, relational extension of those thoughts on Fridays.

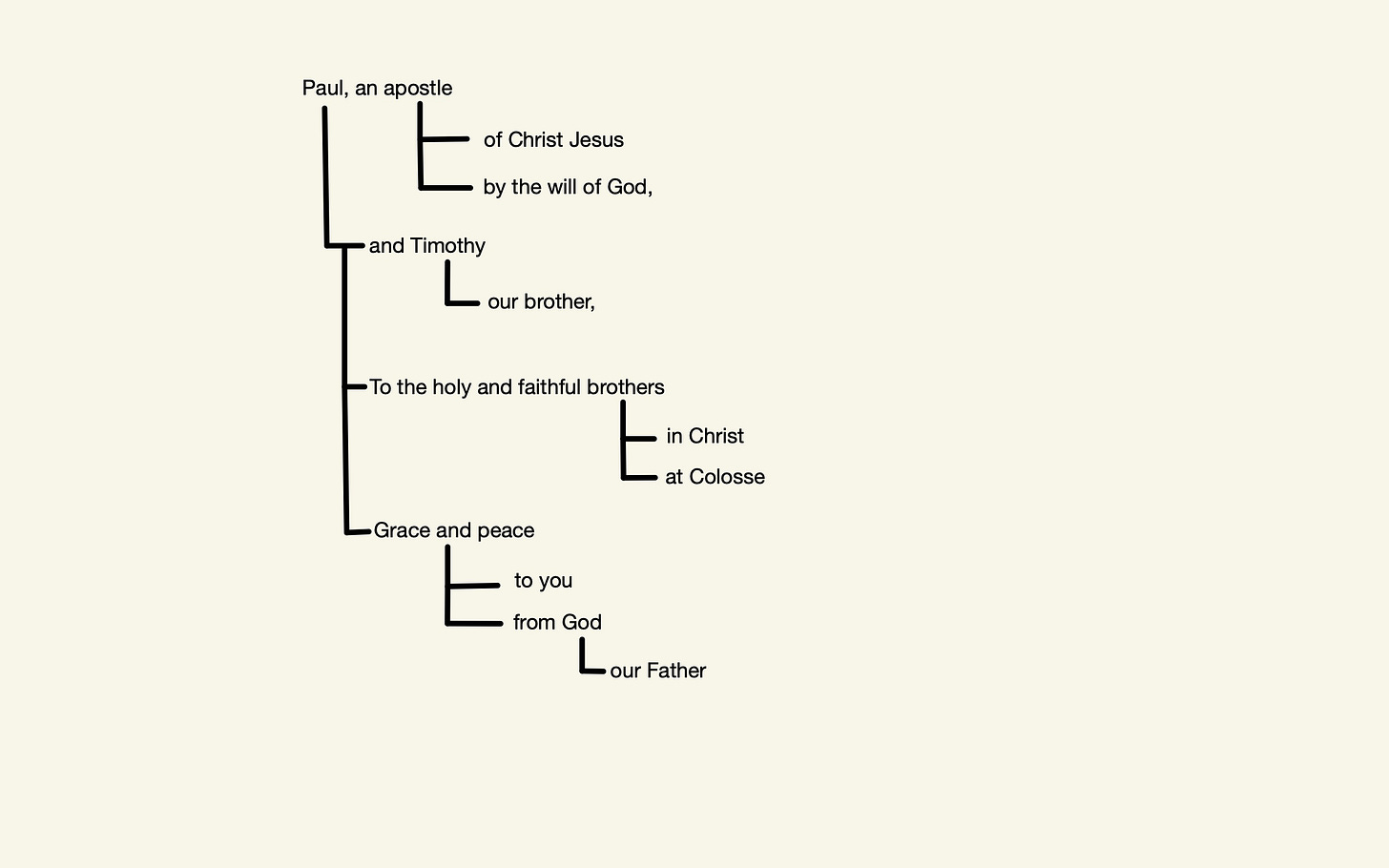

Colossians was the book we used in college back in the early 2000s to learn how to do structural analysis of the text, an approach to biblical study developed by Johannes Louw and Eugene Nida (more commonly known as South African Discourse Analysis) and adapted for our uses by the Rev Dr Andre van Oudtshoorn. Structural analysis, examples of which I’ll show below, slows down your reading of the text; it helps define the main idea of a portion of the surface text from its colour, so that you can discern the semantics of the text; it helps you spot rhetorical devices that a quicker reading of the text might miss, from poetic structures inherent in Hebrew poetry (such as inclusios and chiasms) through to rhetorical devices such as repetition, echoes, parallels and so on. Spotting these rhetorical devices can provide big clues about the text’s meaning or an author’s intention.

Author’s intention — this is a big subject, which I won’t get into here (although the impact in philosophy and literary criticism of debates over author’s intention and whether we can ever know it, or even if it’s helpful to know it at all, will influence some of what I write about the text). All I’ll say here is that in my experience using structural analysis on a range of New Testament and Old Testament books, because it leans so heavily on rhetorical analysis (identifying the intentional rhetorical devices and structures within a text) it favours the pursuit of what was in the author’s mind in terms of a communication act behind two parties, which is what most of the New Testament is — letters from one apostle or another to members of churches. This isn’t the same issue as debates over the historical authorship of a letter like Colossians. There are valid questions about whether Paul or someone else wrote Colossians, but I find such debates as part of an introduction a little mind-numbing (because they’re out of context). The text of Colossians itself raises doubts about a Pauline authorship, and it’s in this context that I would prefer to think about it.

Whatever else structural analysis is, it preserves and respects the sense that what we’re reading was once an encounter between people, an effort to communicate something that the writer thought was wonderful and disruptive and worth sharing. That’s what I want to find in the biblical text when I read it — what is that wonderfully disruptive thing that this writer needed others to know, and how do I best bring the critical tools at my disposal to bear upon the text to find it. My assumption is that although that wonderful thing was communicated in a particular time and place and against the backdrop of a culture very different from mine, there is a way to be appropriately impacted by it in the here and now.

Structural analysis finds that thing by diagramming the flow of the text, so that you can see how parts of it (clauses or phrases or qualifiers) relate to other parts. Think of it like a tree, comprised of a trunk (the main idea) and the branches (the qualifiers, descriptors and colour). The trunk is comprised of complete thought units (one thought unit is a colon, plural cola). Incomplete ideas that branch away from the main trunk are called commata (singular comma). So structural analysis is initially the process of separating cola from commata.

Here’s an example of Colossians 1:1-2 where the main idea (the colon) has been separated from the commata.

I say an example because there’s not exactly a “right” way to do this. It’s an aid to your understanding — which doesn’t mean that you’re free to make up whatever you want about the text, but it does mean there might be a more helpful way to diagram it. My structural diagramming of the text is always provisional, but especially on the first pass. Quite often my work on the text reveals that I’ve drawn aspects of the tree in an unhelpful way.

But in this diagram, note how the main idea follows the branch running down the left side, which is the colon. In other words, without the qualifying phrases and ideas, this is a simple greeting:

Paul and Timothy to the holy and faithful brothers; grace and peace to you from God.

It’s on closer inspection, and with the aid of the diagram, that we see it’s not quite so simple.

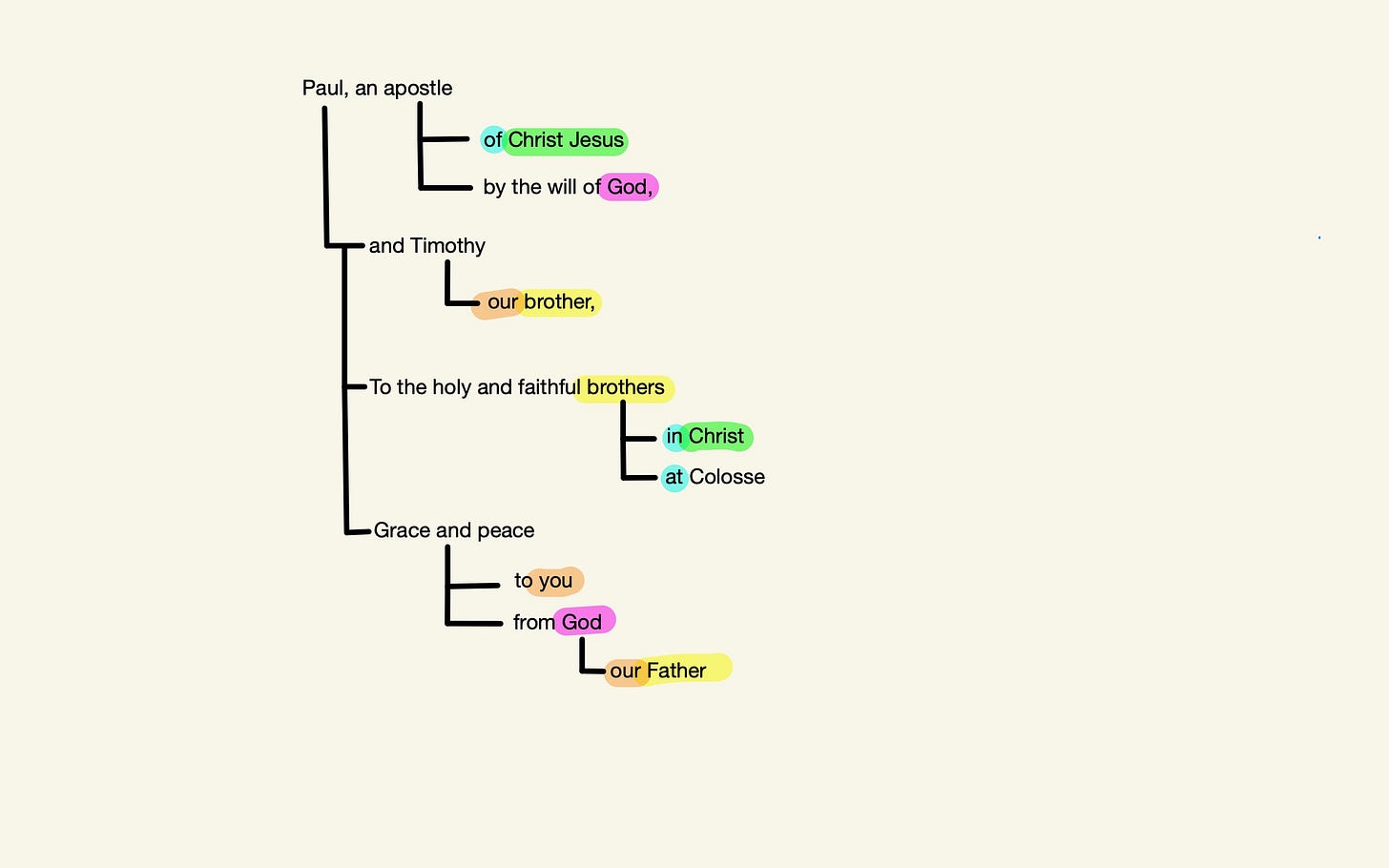

Before we go there though, we’re going to take a couple more steps with the diagram itself. First, we’re going to colour code words that fall within the same semantic fields, so that we can more easily identify echoes, parallels, and repetitions.

You can see in this picture that I’ve colour coded “Christ Jesus” and “Christ” (the obvious one); I’ve marked where God is mentioned (twice); but then I’ve also colour-coded “brothers” (also used twice) and “Father”, because they fall within the semantic field of kinship relations; I’ve also separated out “our” and “you” because they identity the parties in the discourse, and immediately suggest a sense of communal belonging — they also mark this as an I-Thou encounter that is anchored in time and place (in other words, this isn’t a generic “you” that Paul is writing to, but a specific group of people with specific circumstances and issues); I’ve also colour-coded the prepositions “in” and “at”, because even in the structure of the text you can see that they form a parallelism, and it might suggest something about how we unpack that section of the greeting.

Once I’ve done this, I’m ready to evaluate the stylistic impact of those rhetorical/poetic/literary/grammatical devices. What are they telling me? How are they influencing my reading? What can I learn about the intended first readers of this letter to get some idea of how this text (and the structure of it) might have impacted them? This latter step will require some research outside the text itself about the community at Colosse: what can I learn from commentaries or New Testament introductions to help me understand them more in order to have a better appreciation for what the stylistic impact would have been on them.

This is where I learn that Colosse at the time of Paul stood on an important trade route, which meant that it was not only wealthy but it was exposed to a spectrum of ideas, philosophies, theologies. But at the time of the letter, the trade route had been diverted away from Colosse and it was already suffering a decline in commercial and social importance. As for the church, it was meeting in the home of Philemon (yes, that Philemon) and its members were mainly Greek and converted Jews. We’ll say more about this in future articles.

Having taken these fives steps, I’m ready to start musing on the text and what it communicates:

I’ve diagrammed the text to show its cola and commata

I’ve determined the main idea of the text (the colon)

I’ve identified and marked the semantic fields

I’ve noted the stylistic patterns

I’ve evaluated the stylistic impact

So what am I seeing in this text that bears further thought (and will be the subject of Wednesday’s article)?

Some notes:

I’m seeing that “Christ” qualifies two quite important descriptors in this greeting: it qualifies both the apostleship of Paul, and the “brother” status of those in Colosse. In other words, there’s a bond here that transcends the communication act itself; it also transcends any sense of status between the letter writer and the letter recipients. The apostle and the recipients of the letter are “of” Christ and “in” Christ. Apostle in this sense doesn’t transfer greater importance, since they both fall under the authority of Christ. Nevertheless, the same Christ who defines the Colossians as brothers is the one for whom Paul is an apostle, by the “will of God”. The clear implication: you fellas need to listen to what I’m about to say.

I’m also seeing the use of “brother” and “brothers” to establish another link between the writer and the readers. Timothy is described as “our brother” — “our” here could mean the brother of Paul and the other apostles, but it could also mean Paul, the apostles and those at Colosse. I’d lean to the latter because of how they are also described as “brothers”. This observation is made more potent when read in the light of God being qualified as “our Father”. Now you might counter this by pointing out that God is commonly referred to in the New Testament as “our father”. But the point is that our stylistic analysis has identified a theme of kinship relations in just the first two verses of this particular letter. It might prove to be important in how we unpack the theology of the rest of the text; it might not. We’ll hold it lightly until we know for sure. But I’m inclined to think it is structured this way for a reason. The letter writer and the letter recipients are brothers, but it’s a very particular type of brotherhood — it’s one that exists only because of the fatherhood of God, as well as the “of-ness” in Christ Jesus of the apostle, and the “in-ness” in Christ of those at Colosse. Already, I’m getting hints of a trinitarian formulation to how the author sees the connections between himself and Timothy, the Colossians, Christ and the Father.

One more thing: the parallel structure of the holy and faithful brothers being qualified as “in Christ” and “at Colosse”. This is by no means the main idea of this introductory passage, but it’s a nice bit of colour that bears drawing out. How do these two qualifiers interface? Can they coexist? Where do they conflict? Where do they merge? What is it to be holy and faithful in Christ, but also holy and faithful in Colosse? If I’m reflecting on this text’s impact on me, personally, I’m asking: what does it mean to be in Christ and also in Auckland? What does that look like? Does one have priority over the other? Do they have to be in conflict or can they coexist quite nicely? In my own life, have I privileged one above the other? When people encounter me, do they get a sense of someone in Christ, or am I defined more by my behaviours as a citizen of Auckland? And does the answer to that question even matter? Extending that idea, how am I holy (set apart) and faithful (dependable and steadfast)? Are those things witnessed in my behaviours, in Auckland, or are they conferred on me by Christ? And should there be a difference?

At this stage of my work on the text, I’m typically asking these questions rather than coming up with final answers. There’s quite a way to go in the book — I’m only in the first two verses after all. But already I’m getting a sense that there’s something going on in this encounter between Paul and the people at Colosse that may impact how I understand myself as a Christian located in a particular time and place.

I want to think more on this idea of brotherhood as well; and specifically brotherhood in light of the fatherhood of God. It looms large in the text for me, so I want to reflect on the idea of brotherhood and sisterhood. When I think about brotherhood from how I observe it in culture, as an ideological marker, something that binds a group together, often at the expense of others, or in conflict with other prevailing ideologies, I have to admit I’m a bit troubled by it. I don’t see brotherhood as a positive thing.

I recently binge-watched Sons of Anarchy — all seven seasons of it. I loved it and was troubled by it in equal measure. Thankfully, its final imagery, so powerfully alluding to the gospel, redeemed the whole experience. However, that outlaw motorcycle club culture left me with very uneasy feelings about “brotherhood”. But brotherhood as defined under the fatherhood of God? Surely - hopefully - that’s something else entirely. I’m interested in what Paul is hoping to achieve by establishing their common brotherhood at the very beginning, and how the fatherhood of God shapes our understanding of what it is to be brothers and sisters in Christ.

That’s where we’ll head on Wednesday.

Talk about heavy lifting! Putting that exegetical training to good use.